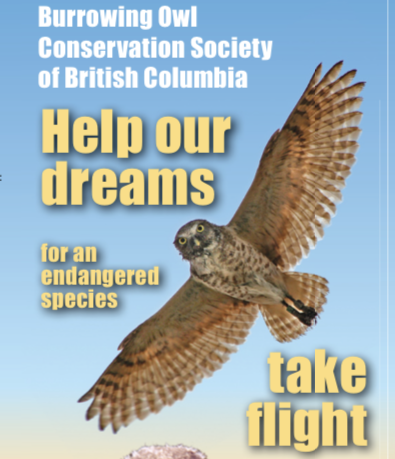

BURROWING OWL CONSERVATION SOCIETY of BC

We build and maintain nesting burrows in conservation areas for burrowing owls. Most of our conservation work is done on private land. None of this would be possible without the support and interest of landowners.We are grateful for their continued participation.

If you would like to donate land or participate as a partner in our conservation program, please email us bocsbc@gmail.com

If you would like to donate land or participate as a partner in our conservation program, please email us bocsbc@gmail.com

Owls are raised and cared for by trained staff in dedicated breeding facilities. The birds have spacious flight pens and high quality food allowing them to have the greatest chance of success before release to the wild. These centres are far apart in order to protect the birds in case of disease or disaster. They are located at: Kamloops, Port Kells and Oliver.

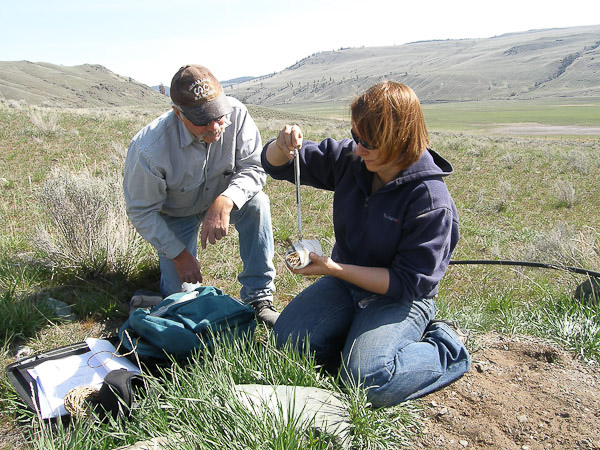

After a year in the breeding facility young owls are tagged, paired and released to a nestiing burrow in the wild. We monitor their success and report to BC government. If you see a burrowing owl in the wild we would love to hear about it and see any photograph that you may have taken. Please let us know bocsbc@gmail.com .Include details of the location, time, date, weather conditions and what the bird was doing. If you took a photograph please include it. Tell us if you noticed any bands or coloured marking on the legs.

We support and promote educational and interpretation programs to inspire future generations who will conserve these iconic grassland birds.Our brochure with conservation information is available for download.

OUTREACH

Download our BOCS BC pamphlet with information about conservation and protection of burrowing owls.

Read the current edition of Pellet Post Newsletter

WInter 2024

Back issues of Pellet Post with burrowing owl news and conservation information can be viewed here:

Archived Pellet Post newsletters

WInter 2024

Back issues of Pellet Post with burrowing owl news and conservation information can be viewed here:

Archived Pellet Post newsletters

Lauren and our ambassador owl are available to visit schools and community events to help raise awareness of the significance of burrowing owls and the importance of conserving grasslands. If you have an event or want to help us fundraise, please contact us bocsbc@gmail.com

Owls in the News

BOCS struggling as food costs are doubling to feed endangered species they care for in Oliver

Price hikes for food are hitting everyone’s wallets, including the Burrowing Owl Conservation...

Burrowing owls returning to Thompson Okanagan nests after migration to Mexico

Driven by warmer weather, one of B.C.’s most endangered birds is returning to their underground...

Burrowing owls released onto Alberta prairie as part of efforts to bolster endangered species

Canadian populations of the owls have declined more than 90% over last 40 years CBC News · Posted:...

Captive breeding only works when animals can go home

By David Suzuki with contributions from Ontario Science Projects Manager Rachel Plotkin B.C. is...

Owl evacuees get comfortable in new home in Kamloops

Jesse Johnston CBCNews · Posted: Aug 17, 2019 9:00 AM PT It's not unusual for birds to migrate but...

She did it for love.

She did it for love: Rare wild owl tries burrowing into Manitoba enclosure to find mate Researcher...

Nearly 100 juvenile burrowing owls take first steps into the wild

Residents of B.C.'s Interior shouldn't be alarmed if they start seeing a bunch of owls flying...

Lauren Meads: Top 40 Entrepreneur

This year, Okanagan Edge and the Kelowna Chamber of Commerce have partnered to showcase some of...

Global Owl Project in Umatilla Oregon

As founder of the Global Owl Project, David Johnson works with 450 people in 65 countries to...

WildLens Eyes on Conservation

Burrowing Owls (Athene cunicularia) are a small (150-180 g) species of owl that nests in the...

Species Spotlight - Burrowing Owl

Common name: Burrowing Owl Latin name: Athene cunicularia Status under SARA: Endangered, 2006...

Digging for Owls

BC Wildlife Park video on the Burrowing Owls

Fun Facts

Meet our Field Team

Lauren Meads

Executive Director

Lauren is passionate about animals and has Master's of Science in Applied Animal Behaviour from the University of Edinburgh Scotland. She has a great commitment to the conservation of burrowing owls.

Lia McKinnon

Field Biologist

Lia has been with the project for several years and confidently handles owls and their chicks as part of the spring and summer field program.

Charyl Omelchuk

Field Biologist

Charyl works with the burrowing owl program in Kamloops. Her owl catching skills are unsurpassed and she is an asset to the program

Tracy Reynolds

BC Wildlife Park

Tracy is Animal Care Supervisor at BCWP. She looks after the burrowing owl captive breeding program in Kamloops.

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Mike Mackintosh - Chair of the board and Founder

Jim Wyse - Vice Chair, Finance and Fundraising Director

Elaine Humphrey - Secretary and Education Director

Aimee Mitchell - Science Director

Tracy Reynolds - Captive Director

Cliff Lemire - Volunteer and Membership Director

Jack Madryga - Director at Large

John Gray - Director at Large

Steve Church - Director at Large

Dave Low - Director of Lac Du Bois